The story of the Wright brothers’ first powered flight in 1903 is widely known, but historians agree they wouldn’t have entered the history books without the help of their extraordinary sister. Katharine Wright has been called “aviation’s unsung heroine” and the key to the success of her famous brothers, Orville and Wilbur. In honor of Women’s History Month, read about the accomplishments of Katharine Wright, the forgotten Wright sibling.

Katharine Wright, Aviation’s Unsung Heroine

Running the Wright Household

Katharine Wright was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1874, the only daughter of Susan and Milton Wright. She had four older brothers in total, but was so close with Orville and Wilbur that historians speculate the trio made a secret pact in their youth to never marry and instead spend all their time together; according to PBS, she “was essentially the only female figure in Orville and Wilbur’s adult lives.”

The Wrights’ father was often traveling in his job as a church leader, and when Katharine was 15, their mother died of tuberculosis. As a result, she was forced to take over the responsibility of managing the family household. She became especially comfortable talking to all manner of people, a result of her often playing host to her father’s many guests and other local figures in the Wright home.

While Orville and Wilbur were shy, reserved, and socially awkward, Katharine became very outgoing, engaging, and confident in her role as head of the house. As Katharine’s biographer wrote, Orville and Wilbur were “not the kind of guys you would want to invite to dinner. You could picture them coming over for dinner and not saying a word.” Because of this, they would come to rely on Katharine’s support as they pursued their business interests and their dream of powered flight.

Katharine was the only one in the family to get a college degree. She graduated from co-ed Oberlin College in 1898. It took her five years to complete her degree, because she left to help nurse Orville back to health when he took ill from typhoid fever in 1896. By 1899, she had a job as a substitute teacher; By 1901, she was teaching English and Latin full time at Steele High School. As she pursued her own career, she continued to support her brothers as they became involved in more and more mechanical enterprises, including operating a printing business and a bicycle repair and sales shop. When Orville and Wilbur became interested in the budding field of aeronautics, Wright-Brothers.org wrote Katharine “watched her brothers evolving work on the problem of manned flight with a mixture of interest, annoyance, humor, encouragement, and admiration.”

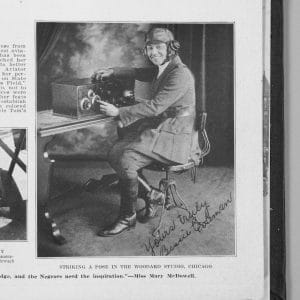

Katharine Wright (Public Domain Photo)

The Path to Flight

While Orville and Wilbur worked on their experimental glider down in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, it was Katharine Wright who kept their affairs in order so they could pursue their dream. She watched over their businesses, paid bills, collected receipts, and responded to newspapers and scientific inquiries as her brothers became more notable among the community of inventors and entrepreneurs attempting flight.

In 1901, however, her brothers returned home from North Carolina in dour spirits because their glider hadn’t performed the way they expected. Wilbur, frustrated at the results, claimed that “Man won’t be flying for a thousand years.” When Wilbur was invited to speak at a meeting of the Western Engineering Society about their experiments, he felt like a failure and planned to refuse the invitation. That’s when Katharine stepped in.

She convinced Wilbur to accept the invite, realizing the importance of the opportunity to get her then-unknown brothers and their experiments before the larger aeronautical community-as she wrote to her father, “I nagged him into going.” Katharine found Wilbur a better suit and helped her nervous brother practice his speech. It all paid off, as the well-received speech and the public exposure resulting from it inspired a new fervor in Orville and Wilbur.

“The flying machine is in the process of making now,” Katharine Wright wrote. “Will spins the sewing machine around by the hour while Orv squats around marking the places to sew. There is no place in the house to live but I’ll be lonesome enough by this time next week and wish that I could have some of their racket around.”

The brothers built a wind tunnel to test over 200 different wing designs, constructed a new Wright Flyer, and finally achieved powered flight on the dunes at Kitty Hawk in 1903. When they moved their experiments back to Ohio, Katharine would round up other teachers to help set up the launching platform and equipment. By 1905, Orville and Wilbur had a more practical flying machine, the Wright Flyer III, that flew for 24 miles. All of this progress would not have been possible without Katharine’s intervention, assistance, and support.

“I think I know every mistake and every success that the boys have made,” she would tell an interviewer in 1909. “If there are some little details which they cannot recall, that is my business. I know everyone who has called at the shop in Dayton. One of my duties is to guard my brothers’ interests.”

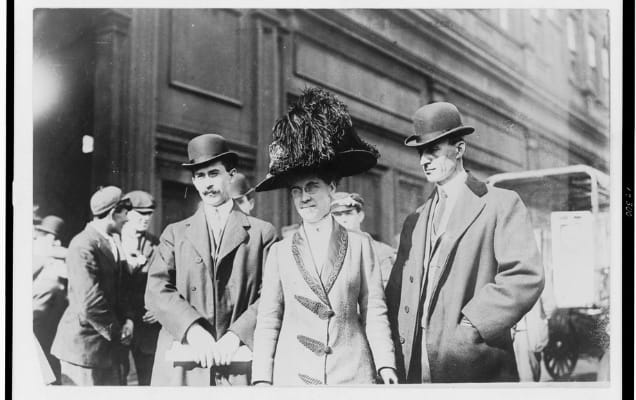

(Public Domain Photo)

Building the Family Legacy

Now that Orville and Wilbur had built and perfected a successful flyer, their efforts turned to marketing and selling their machines. To do this, they relied on Katharine’s connections and charm to win over investors and potential buyers. “Neither Wilbur nor Orville, because they were so shy, were especially good at schmoozing the people who could buy their airplanes,” the Wright Brothers Online Museum writes. “Katharine, however, provided the social chemistry the Wrights needed to make their enterprise work.” Five years after their first flight, the Wrights had caught the interest of both investors in Europe and the U.S. Army.

While testing the Wright airplane for the Army in 1908, Orville crashed; he barely survived, but his passenger, Lt. Thomas Selfridge, would become the first person killed in an air accident. Katharine rushed to Orville’s side and stayed with him night and day. One Army surgeon was later quoted as saying, “It is dubious whether the aeroplane inventor would have survived his injuries had it not been for the presence and loving care of his sister.” With Wilbur away in Europe, she became more involved in the family airplane business and even helped investigate the crash that nearly took her brother’s life. She took emergency leave from her teaching job and would never return to it again.

Soon, Katharine would experience a brush with celebrity. Wilbur, worried sick about his brother and missing his sister, wrote the pair and asked them to join him in Europe to help him generate interest there in their flying machines. Katharine wanted Wilbur to return home, but Wilbur realized that he and Orville, awkward as they were, would need their sister’s social grace to make a good impression on European business elites and royalty. “We will be needing a social manager and can pay enough salary to make the proposition attractive, so do not worry about the six per day the school board gives you for peripateting about Old Steele’s classic halls,” Wilbur wrote. Soon after, in 1909, Orville and Katharine headed to Europe by steamship.

On the whirlwind European tour that followed, Katharine introduced her brothers to counts, dukes, and kings-including King Edward VII of England, King Victor XX of Italy, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Germany, and King Alfonso XIII of Spain, who would call her the “ideal American.” The Wright Brothers Online Museum writes, “Once, when preparing to meet the King of Spain, she practiced the proper curtsey with the wife of an English baronet. But when King Alfonso XIII showed, she forgot herself and greeted him American-style with a simple handshake and a brilliant smile. The king was won over.”

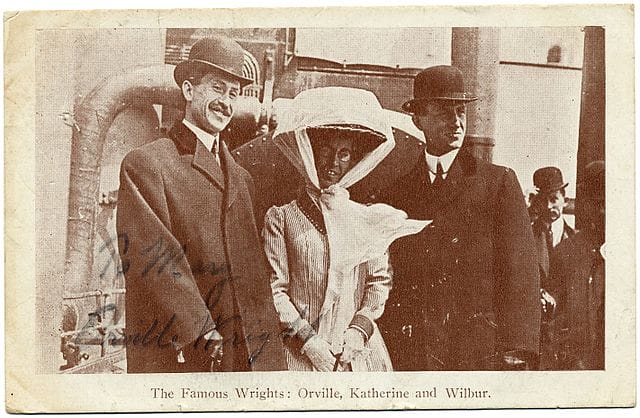

During this trip, Katharine took her first flight in her brothers’ flying machine and became the third woman to fly in an airplane. The next time she flew, the audience included King Edward VII; it was a powerful statement to a powerful figure that women could take to the skies, too.

In 1909, Katharine was the subject of a fawning World Magazine article titled “The American Girl Whom All Europe Is Watching.” “Few know what she has done,” the piece read. “Few know how hard she has worked to make her brothers’ machine a working accomplishment. But the Wright brothers realize it all and pay her due tribute- hats off, then, to Miss Katherine Wright, who has ever been the mainstay of her brothers in their many efforts to conquer the air.” Before leaving Europe, Katharine was awarded the French Legion of Honor along with her brothers; upon returning home to Dayton, the trio were met with a homecoming celebration, and even got to meet President Taft.

During this time, Katharine assisted her brothers in patent litigation and a battle over the claim to being first in flight. The Smithsonian Institution credited Samuel Langley as the inventor of the airplane, even though his 1903 aircraft was only able to fly after Glenn Curtiss made major modifications to it in 1914. Katharine dedicated herself to proving that her brothers were first; in one of her letters from the period, she vowed the Smithsonian would be “shown up for joining in such a fraud.”

When Wilbur died after a bout with typhoid fever in 1912, his passing was blamed in part by Katharine on overwork stemming from the patent battle. In another letter, Katharine wrote, “I am determined that the country shall know that Wilbur was killed by the fights he had to make to keep from having everything stolen, that the last years of his life were worse than thrown away.”

Katharine Wright takes her first flight. (Oberlin, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Split with Orville and Later Life

Why have so many not heard of the contributions of Katharine Wright, who historians agree was essential to Orville and Wilbur’s pioneering aviation achievements? The answer may be due to the deterioration of her relationship with Orville-and Orville’s cruel decision to cut her out of the story.

After Wilbur’s death, Katharine moved in with Orville and their father, Milton, who passed soon after. Katharine wasn’t just the Wright Company secretary and Orville’s important business partner-she was also his best friend and basically the shy, socially awkward inventor’s only connection to the outside world. Without her, he would have to engage with and speak to others himself, a task he hated. So, Orville remained extremely jealous and guarded about his relationship with his sister.

Meanwhile, Katharine became active in the women’s suffrage movement, helping to organize a Dayton Suffrage March that drew 1,300 attendees. She became active in the Young Women’s League and Dayton College Women’s Club, becoming president of both. She became a Trustee at Oberlin College, only the second female trustee in the institution’s history-and while there, she revived correspondence with the man who would become her husband, her former classmate Henry “Harry” Haskell.

As Katharine and Harry courted, Katharine was afraid to tell Orville about their relationship because of how he might react. She kept their plans to marry a secret for months and months before she finally made Harry tell Orville, who felt angry, betrayed, and abandoned-so much so that he refused to attend their wedding or even speak to his sister.

A sulking Orville went on a mission to keep Katharine’s name out of the Wright brothers’ achievements. As NPR reported in 2003, an Associated Press memo from a few months after Katharine and Harry’s wedding was found in an archive which reads: “We have accepted as a true story that Mrs. Katharine Wright, sister of the Wright Brothers, contributed financially and scientifically to the first success of the airplane. The Wright family has shown that this is not true. Please see to it that any item offered in our service refrains from accepting as true this very pretty story of sisterly support in this achievement.”

Katharine and Orville would only end up seeing one another one more time-when Katharine was lying on her deathbed in 1929. Upon his death in 1948, Orville left $300,000 to Oberlin College in her honor. Today, the school’s Wright Laboratory of Physics bears her name, and students walk past a marble fountain commissioned by her late husband.

Katharine provided her brothers with the support they needed to make their breakthroughs in flight; Orville once was quoted as saying that “When the world speaks of the Wrights, it must include our sister. Much of our effort has been inspired by her.” Today, the National Aeronautic Association honors those who have “contributed to the success of others, or made a personal contribution to the advancement of the art, sport and science of aviation and space flight over an extended period of time” with the Katharine Wright Memorial Trophy.

Read More about Women’s Aviation History

BESSIE COLEMAN, THE FIRST BLACK WOMAN TO EARN A PILOT’S LICENSE