Pioneering aviator Bessie Coleman pursued her dream of taking to the skies against all odds, shattering aviation’s racial and gender barriers in the process. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about the incredible exploits of “Queen Bess,” the first African-American and Native American woman to earn a pilot’s license.

Life And Legacy Of Bessie Coleman

A Dream To Fly

Born to sharecroppers in Atlanta, Texas in 1892, Bessie Coleman grew up helping her parents pick cotton along with her 12 siblings. Determined to get an education and rise above her station, Coleman graduated high school and even attended a semester of college at Langston University before heading to Chicago as part of “The Great Migration” from the South along with millions of other African Americans. There, she worked as a manicurist while living with her older brothers.

An avid reader, Coleman was dazzled by stories of daredevil aviators, the rock stars of their time, returning from the fighting in Europe in WWI. At a moment when racism was rampant-Chicago experienced one of the worst race riots in history in the summer of 1919-she began to imagine herself entering the field of aviation as a way of inspiring and benefiting African Americans everywhere. When Coleman’s older brother who had served in France returned home with stories of women in more liberal Europe flying airplanes, Coleman became determined to become a pilot herself.

She began applying to aviation schools across the U.S., but was repeatedly denied, as they all refused access to both African Americans and women. But Coleman didn’t give up-as she said, “I refuse to take no for an answer. If I can create the minimum of my plans and desires, there shall be no regrets.” Half a world away, she found a school willing to teach her to fly.

Journey Overseas

Seeking additional help, Coleman reached out to Robert Abbott, owner of an influential black newspaper called the Chicago Defender. She convinced Abbott, known as “the father of black journalism,” that it was important to have a black woman pilot. Impressed (and recognizing a great story in the making), he suggested she enroll at a flying school in France.

After teaching herself French, Bessie Coleman set sail for Paris in November of 1920. She trained for months at the Ecole d’Aviation des Freres Cadron, a prestigious flight school run by plane designers and aviators Gaston and Rene Caudron. In the early days of flying, aviation was still extremely dangerous, and Coleman persisted even after witnessing the deaths of several of her fellow students. When she arrived back in the United States in September 1921, she brought with her the international pilot’s license she had earned as well as a commitment to encouraging more African Americans to fly.

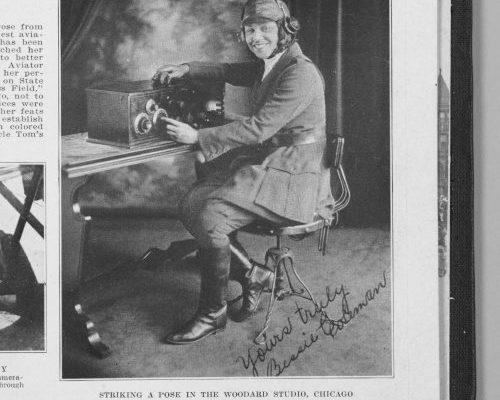

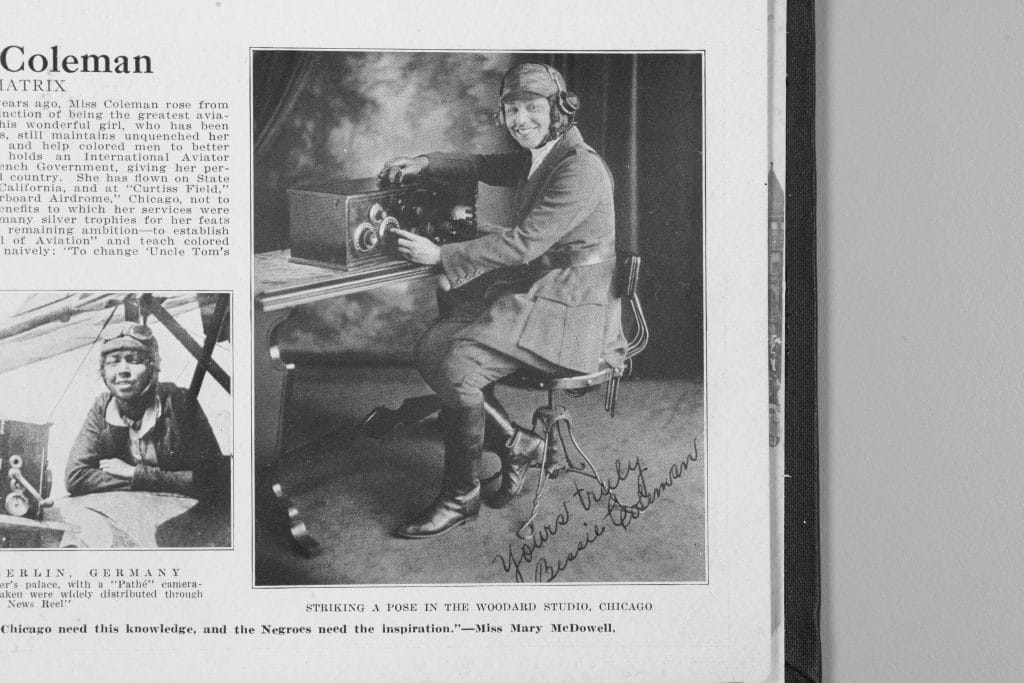

Bessie Coleman in her flying uniform. (New York Public Library Public Domain Archive)

What she found was a country still unwilling to hire her or even sell her a plane. But she saw an opportunity in the “barnstorming” craze-if she was to find employment, Coleman knew she would have to learn to pull off the dangerous stunt tricks performed by aerial acrobats at barnstorming exhibitions across the country. So, she went back to Europe, this time training with veteran WWI flying aces and legendary Dutch airplane designer Anthony Fokker.

Returning stateside, Coleman began a series of thrilling air shows where she performed for thousands of people, both black and white. With her new skills-and with the Defender celebrating her performances-Coleman’s fame took off.

A Fearless Personality

Bessie Coleman’s intense drive was what allowed her to pursue her dream and achieve her goals; as she famously put it, “Every no takes me closer to a yes.” According to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Coleman was fiercely independent:

Coleman steadfastly pursued her dream and lived her own independent, unorthodox life-including firing male managers and refusing movie roles she felt were demeaning, reportedly saying “No Uncle Tom stuff for me,” in reference to playing a subservient Black woman. Like her contemporary Amelia Earhart, Coleman was not afraid to be different. She was a fearless personality who defied odds and stepped on toes to claim her space as an aviator.

While she was largely ignored by the mainstream press, she was a star in the pages of the Defender and other black newspapers, gathering legions of fans to whom she was known as “Queen Bess” or “Brave Bess.” She was an expert at self-promotion, making appearances in a military-style uniform with an officer’s belt, leather boots, and leather helmet and goggles-and often embellished her already-impressive story during interviews. She performed incredible barnstorming stunts like tailspins and loop-the-loops for large crowds, made public appearances where she encouraged other African Americans to fly, and, in the midst of Jim Crow, “refused to perform in airshows where blacks were not allowed to use the front entrance.”

Even after crashing her brand-new Curtiss JN-4D “Jenny” biplane in 1923, she was undeterred. She was pulled unconscious from the wreckage and spent three months in the hospital, having broken a leg and several ribs. Her message to the world from her hospital bed was, “Tell them all that as soon as I can walk I’m going to fly! And my faith in aviation and the use it will serve in fulfilling the destiny of my people isn’t shaken at all.”

A Curtiss JN-4D “Jenny” Biplane like the ones flown by Bessie Coleman. (New York Public Library Public Domain Archive)

A Tragic Final Flight

In April of 1926, Bessie Coleman had finally raised enough money for another brand-new airplane, and took it for a test ride in Jacksonville, Florida. A white mechanic, William Willis, was flying the plane while Coleman scouted the land below for a good spot to perform a parachute jump. In what was later found to be an accident, a loose wrench jammed the JN-4D’s controls and threw the plane into a nosedive at 3,000 feet. Without a seatbelt, Coleman was thrown from the plane and killed when it flipped over. Willis was killed when the plane crashed into the ground.

After just five years, Coleman’s trailblazing aviation career was tragically cut short. PBS says about 10,000 mourners paid their final respects to Coleman, and in Chicago, her funeral services were presided over by famed activist Ida B. Wells.

A Lasting Legacy

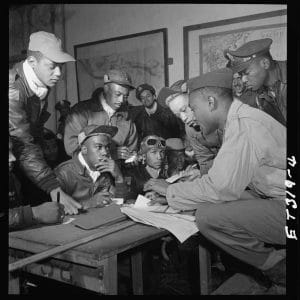

The National Aviation Hall of Fame notes that Coleman only received the attention she truly deserved after her tragic death, but it’s undeniable that her accomplishments in early aviation paved the way for generations of future black aviators. Her dream of opening an aviation school for African Americans was realized in 1929, when Lt. William J. Powell founded the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles in her memory, allowing both men and women to apply.

If you fly into O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, the city Coleman called home, you’ll find yourself on Bessie Coleman Drive. To this day, during an annual ceremony, pilots fly over Lincoln Cemetery and drop flowers on her grave. The tradition was started in 1931 by a group of pioneering black aviators called the Challenger Pilots’ Association of Chicago; this early flight club included several other African-American aviation legends who carried on Coleman’s mission, including Cornelius Coffey, Janet Bragg, and Willa Brown.

The Tuskegee Airmen fought The enemy abroad and racism at home

Cornelius Coffey And The First Black Aeronautics School

Celebrating Black History: Elevate Every Journey with Magellan Jets

Here at Magellan Jets, we honor the rich legacy of Black pioneers in aviation and beyond.

Experience private aviation with a company that values every journey. Contact us today to talk about our full range of private aviation solutions.