The Tuskegee Airmen were the United States’ first African-American military pilots. They flew missions against the Axis powers during WWII while simultaneously battling racism, bigotry, and intolerance from their own side. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about this highly decorated group of black combat aviation pioneers.

The Tuskegee Airmen: America’s First Black Combat Pilots

Origin and training

As war in Europe loomed on the horizon, the U.S. faced a pilot shortage. Black pilots were ready and willing to serve, but still faced barriers to admittance and training because the U.S. military was still a segregated force. When the government announced an experimental program to train civilian pilots for the military, prominent black newspapers, civil rights leaders, and the NAACP advocated for African American pilots to be included, but they ran into resistance.

Finally, in 1941, a Howard University student named Yancey Williams sued the War Department because the Army Air Corps had refused to admit him due to his race. This lawsuit opened up military aviation to African Americans to the first time-however, even though figures like Cornelius Coffey pushed for full integration and said they would “rather be excluded than to be segregated,” the Corps would only accept black pilots into all-black units. Now, black pilots came from all over the country for military training.

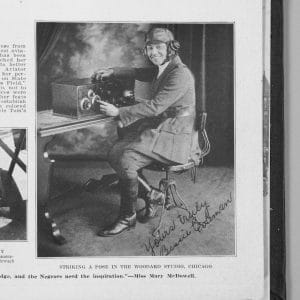

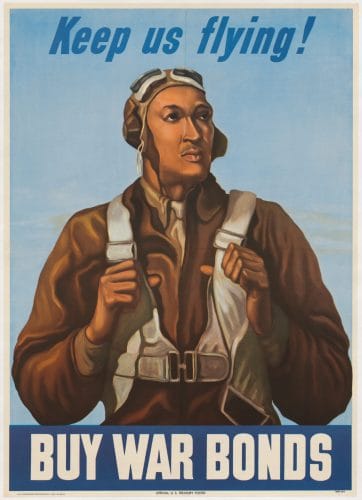

A 1943 poster created by the US Treasury Department during WWII depicting Robert W. Diez, an African American Tuskegee Airman, pleading for Americans to buy war bonds. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

The Army Air Corps soon established a training center for the black pilots at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was near the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), the historic black school founded by Booker T. Washington, which had become one of the country’s centers for training black aviators. The Institute provided the facilities for the pilots and aircraft, while the Air Corps provided planes, uniforms, and educational material in addition to ground and flight training.

Five men graduated from the first class out of an original 13, including Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who was then one of the only two black officers in the entire military. Davis would go on to become the first black man to hold the rank of General in the U.S. Army-but before that, he was given command of the first all-black Air Corps unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

The ‘Red Tails’ Go To Europe

The 99th shipped out to North Africa in 1943. The Allies had just pushed the Germans and Italians out of the continent and were preparing to invade Sicily and later mainland Europe. The Tuskegee Airmen’s first mission would be to bomb and strafe the small island of Pantelleria in between Sicily and Tunisia. Their missions over the enemy-held island would contribute to a historic feat-as Air Force Magazine notes, “the aerial offensive marked the first time in history that an enemy land force was compelled to surrender in the absence of an accompanying ground invasion.” Not long after, Tuskegee Airman Lt. Charles B. Hall became the first member of the squadron to down an enemy aircraft.

At this time, the squadron came under political pressure after its partnered white units complained about the 99th’s performance. Soon, publications like Time Magazine would publicly question their effectiveness. Davis traveled back to Washington, D.C., where he held a news conference at the Pentagon to speak up in defense of his unit. As the website We Are The Mighty writes, there was a lot the complainers had left out-like how the squadron was based further from the front lines than their white peers, excluded from mission briefings, and made to fly older P-40 Warhawk fighters that were slower than German planes. This episode was indicative of the prejudice the unit would regularly face.

A P-51 Mustang featuring the Tuskegee Airmen’s famed “Red Tails” livery, at an air show in California in 2017. (iStockphoto)

When the 99th was sent back to Italy, they became part of the all-black 332nd Fighter Group. The 332nd was made up of three more squadrons of Tuskegee graduates, the 100th, 301st, and 302nd. These units began flying the famed P-51 fighter, painting the tails and nose cones red-leading to the unit’s nickname, the “Red Tails.” While fighting in Italy, the Tuskegee Airmen helped provide air cover for the Allied landings at Anzio, Italy, and provided safe escort for the lumbering bomber aircraft of the 15th Air Force. The 99th would receive two Presidential Unit Citations for their distinguished performance in the Italian theater. Among their incredible accomplishments was the sinking of a German naval destroyer in the harbor at Trieste, Italy; According to the National Museum of the Tuskegee Airmen, 302nd Fighter Squadron Lt. Gynne Pierson sank the large ship using only his plane’s machine guns.

Late in the war, in March of 1945, the 332nd was flying a bomber escort when they encountered German fighters utilizing brand-new jet engines. Despite being outmatched by the new technology, the Tuskegee Airmen managed to down three of the jets and damage five more without losing any aircraft of their own. Incredibly, the Tuskegee Airmen units flew 200 of 205 of these types of escort missions without the loss of a single bomber.

‘Fighting Two Wars’

As the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum states on its website, “These airmen fought two wars-one against a military force overseas and the other against racism at home and abroad.” They fought for what many called “The Double V Victory,” victory against both fascism and racism. At the time, the racism they faced was institutionalized; much of the military establishment, for example, still believed the results of a 1920s War Department report stating “that blacks weren’t intelligent or disciplined enough to fly a plane.” The Tuskegee pilots underwent training in areas of the country plagued by deeply rooted racism. Tuskegee Airman Connie Nappier told Connecticut Explored that, while attending basic training in Biloxi, Mississippi, one fellow cadet was found killed after he went into town alone and didn’t come back.

When the War Department ordered recreational facilities on military bases to be desegregated, Tuskegee Airmen tested the new policy via nonviolent action. In an incident known as the Freeman Field Mutiny, over 100 black officers were arrested for trying to enter the all-white officers’ club at Freeman Field in Indiana after they had been ordered to stay out. Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall defended some of the officers charged. It took fifty years for the government to officially clear several of the Tuskegee Airmen’s military records of this incident.

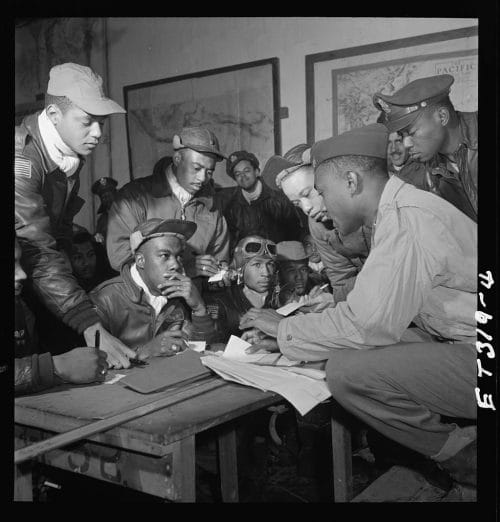

Several Tuskegee Airmen attend a mission briefing in Ramitelli, Italy in March 1945. (Wikimedia Commons/Toni Frissell collection at the Library of Congress)

Chief Master Sgt. of the Air Force George Porter, who served in WWII as a Tuskegee Airman aircraft mechanic, told NPR that racial prejudice made it harder to do his job-“because when we would order parts, they wouldn’t send us the parts, but we learned how to repair our own parts.” Another Tuskegee Airman, Walter Suggs, said many commanders expected the program to fail, saying “they kind of put them in that situation, the Afro-Americans, so they would fail.”

After the war, the pilots who had served in Tuskegee Airmen units still fought for acknowledgement. In 1949, the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group won the newly formed U.S. Air Force’s inaugural “Top Gun” gunnery competition, a feat for which Military.com notes they weren’t recognized for decades.

Legacy

According to the Tuskegee Museum, a total of 992 pilots graduated from the program at Tuskegee Army Air Field between 1942 and 1946, while History.com notes the program also trained “nearly 14,000 navigators, bombardiers, instructors, aircraft and engine mechanics, control tower operators and other maintenance and support staff.”

During the war, Tuskegee Airmen flew a total of 1,578 missions and 15,553 combat sorties, downed 112 enemy aircraft, and knocked out nearly 1,000 rail cars, significantly damaging the German war effort. They lost 66 pilots killed in action or in accidents and 84 pilots killed in training and non-combat missions. During the war, 32 Tuskegee Airmen were taken prisoner. The unit was highly decorated with 744 air medals, including 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, one Silver Star, fourteen Bronze Stars, and eight Purple Hearts.

Historic story markers placed at the observation deck on the hill overlooking Morton Field at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in eastern Alabama. (iStockphoto)

The combat record and civil rights advancements made by the Tuskegee Airmen had an impact on President Truman’s 1948 order to desegregate the military. Lt. Roger Terry, one of the officer charged in the “Freeman Field Mutiny,” said the Tuskegee Airmen’s struggle helped pave the way for those who came after. “We feel-and I think I speak for most of the guys-that it was our advantage that we gave to the Negro people, that there would be no discrimination in the Army Air Force from that time on-at least officially.”

After the war, four Tuskegee Airmen became generals, and many went on to become leaders in business and aviation. When the Army Air Corps became the U.S. Air Force, a new branch of the military, the veteran fliers of the Tuskegee Airmen units were in high demand.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s former training center at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama is now a National Historic Site. In 2008, surviving Tuskegee Airmen attended the Inauguration of President Barack Obama, who has written that “My career in public service was made possible by the path heroes like the Tuskegee Airmen trail-blazed.”

READ MORE ABOUT BLACK HISTORY AND AVIATION

BESSIE COLEMAN, THE FIRST BLACK WOMAN TO EARN A PILOT’S LICENSE