Cornelius Coffey’s pioneering efforts to make flight training available to African Americans helped to desegregate the skies and encouraged thousands of black pilots into aviation in both the military and civilian sectors. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about the man who broke racial barriers to establish the first African-American flight school and the first black-owned airport in the country.

Above photo: Lola Albright and Willa Brown at Chicago’s Harlem Airport, where Coffey and Brown ran their flight school. (Records of the Federal Aviation Administration, National Archives)

Getting off the ground

Cornelius Coffey was born in Newport, Arkansas in 1903, just a few months after the Wright Brothers achieved their first powered flight and captured the imagination of the world. In 1916, when Coffey was just 13 years old, he took his first airplane ride with a barnstorming pilot and was drawn to flying from that day forward. He would later say he believed aviation was a field where the intense racial barriers and segregation of the time would not hold him back.

In 1925, Coffey moved to Chicago to study to be an automobile mechanic. It was there he met his friend John Robinson, another African American who dreamed of one day being able to fly. The two men applied to flight schools across the country, but were constantly denied because of their race—so, they resorted to teaching themselves. In a vacant Chicago lot loaned to them by a Black businessman, Coffey and Robinson used their mechanical knowledge to build a one-seat airplane powered by a motorcycle engine and taught themselves to fly.

While employed as auto mechanics by a white Chevrolet dealer named Emil Mack, Coffey and Robinson continued applying to aviation mechanic schools. Both were accepted into Chicago’s Curtiss Wright School of Aviation, but were dismissed after showing up to their first day of classes when the school discovered they were black. With help from Mack, Coffey and Robinson threatened to sue the school for being denied admittance due to their race. Eventually the school relented, Coffey and Robinson were admitted, and they graduated as two of the top students in their class. Both returned to the school to teach all-black classes—and Coffey became the first African-American man to hold both a pilot’s and a mechanic’s license.

The Challengers

During the Great Depression years, Chicago served as a hub for black pilots wishing to take to the skies—and one of the main reasons was the headway Coffey and his collaborators made in establishing a community of black pilots. In the city that pioneering black aviator Bessie Coleman had called home, Cornelius Coffey and John Robinson established the Challengers Air Pilots’ Association, a group of black fliers who sought to expand the still-limited opportunities for African American aviation enthusiasts. The group took its name from the Curtiss Challenger airplane engine, a popular engine at the time. In 1931, they began the tradition—still carried on today—of flying over Bessie Coleman’s grave as a tribute to the woman who inspired many of them to fly.

After graduating top in his class from an aviation mechanics program in Chicago, Cornelius Coffey was still unwelcome at local airstrips. So he and several other black aviators opened their own airfield and flight school. #BHM #BlackHistoryMonth

— NATCA (@NATCA) February 11, 2020

https://t.co/GkgK9HX9QN pic.twitter.com/7Qd1bKoqL2

The pilots of the Challengers group were, however, still barred from most area airstrips. When Akers Airport, the only field that would accept them, closed, the group established their own airfield. According to Smithsonian Magazine,

In 1931, the group, joined by one or two white pilots from Akers, bought a half-mile-wide tract of land in Robbins, an all-black town southwest of Chicago. There they buried boulders, dropped trees, roughly leveled the terrain, and cobbled together a hangar from second-hand lumber. When they finished, their small fleet of disparate craft—a Church Mid-Wing, an International F-17, and a WACO 9—was parked under the roof at what historians consider the first black-owned airport in the United States.

In 1930s Chicago, pioneering Black aviators improvised, innovated, and overcame societal barriers to fulfill their dreams of flight. Discover their story in the latest episode of our @AirSpacePod: https://t.co/oOCpJmf2Q3

— National Air and Space Museum (@airandspace) June 13, 2021

📷: Challenger Air Pilots Association in 1931 pic.twitter.com/q0tHgnlVry

Completed in 1933, Robbins Airport was only operational for a few months; it was destroyed by a powerful storm later that year. The Challenger group was then invited by a man named Fred Schumacher to use the lower end of his new airport on Harlem Avenue, which later became known as Harlem Airport. Finally, the black aviators had a place to fly—but the pilots were still forced to park their planes in separate hangers from the white pilots and keep on their end of the airfield.

The First Black Flight School

In the mid-30s, Robinson left the United States for Ethiopia, where he used his flying skills to fight against the invading Italian fascist army. Back in Chicago, Cornelius Coffey worked as a mechanic for Schumacher, re-certifying the overhauled aircraft used by the white pilots on the other side of the airfield. Then, in 1938, he established The Coffey School of Aeronautics, the first black-owned and certified flight school in the country.

Coffey hired other pioneering black aviators to teach at his school—including a former student of his, Willa Brown, who was later to become his wife. Brown had been the first African-American woman to earn her pilot’s license in the U.S., but she would be far from the last—as Coffey later noted, “Every 10 students that I took, I had one white student and one girl student in that unit.”

With World War II on the horizon, the U.S. government sensed a need for an increase in military pilots. The Civilian Pilot Training Program was created in 1939 to train new fliers for the Army Air Corps, which was the predecessor to the U.S. Air Force. Coffey and Brown wanted to make sure black aviators were included, so they renamed the Challenger Air Pilots’ Association to the National Airman’s Association (NAA) and focused their group on the goal of getting black pilots into the military. To draw attention to their cause, the NAA organized a publicity flight to Washington, D.C. As a result, seven black pilot training sites were included as part of the government’s training program; Coffey’s school was the only one not associated with a college or university.

A Lasting Impact On Aviation

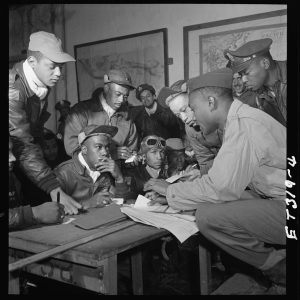

Between 1938 and 1945, more than 1,500 black students passed through Coffey’s school. Many of those pilots went on to join the famed Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American air units to fight against the Nazis in Europe. Coffey, whose school was integrated, initially spoke out against these segregated flying units, saying, “We’d rather be excluded than to be segregated.”

After WWII, Coffey enjoyed a long career as a pilot, mechanic, and teacher. He retired from instructing in 1969, but kept busy as an aircraft inspector for decades. He designed and patented a carburetor heating system that helped keep aircraft flying in inclement weather by preventing icing, and similar devices continue to be used today. Coffey continued to fly until 1992 and passed away two years later at the age of 91. In Chicago, pilots encounter his legacy daily when they use the “Cofey Fix,” an aerial navigation intersection named after him that is located over Lake Calumet and helps guide entry into Midway Airport.