Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.’s leadership of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during World War II helped lead to the desegregation of the U.S. Military. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about this four-star general whose career spanned three wars and smashed racial barriers.

Benjamin O. Davis Paves The Way For Desegregation In The Military

FOLLOWING IN HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS

Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr. was born in Washington D.C. in 1912. His father, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., was one of only two black officers in the U.S. Army at the time, and would eventually become the first African American General Officer in the entire U.S. Armed Forces. As a child of a military family, Davis Jr. moved around often, experiencing the racism and bigotry faced by African Americans across the country. The elder Davis, his military career stymied by segregation, instilled in his son a deep desire to fight for the end of the practice. He was determined to follow his father into military service and fight for equal inclusion for African Americans.

Davis Jr. was taken by aviation at an early age. When he was just 13, he took a ride with a barnstorming pilot at D.C.’s Bolling Field, cementing his desire to become a pilot. However, African Americans were still largely barred from flight training opportunities, so he set his focus instead on attending the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. After a few years of studying at the University of Chicago, he received a recommendation to attend West Point from Rep. Oscar S. De Priest, who was at that moment the only African American Representative in the U.S. Congress.

Gen. Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr. (Public Domain photo)

At the time of his graduation, Davis Jr. was only the fourth African American graduate of West Point in its history, and the first in the 20th century—the first since the Reconstruction era. As Air Force Sustainment Center Historian Howard Halvorsen wrote, “His four years there were not pleasant;” he roomed alone, took his meals alone, and had no friends among his colleagues. He was “silenced” by the other cadets, meaning they only spoke to him on official business.

Despite the fact Davis graduated in the top 20 percent of his class in 1936, the segregation of the armed forces still kept his dream of becoming a pilot at bay. There were no Black air units, so he was denied his requests for flight training and instead sent to the infantry. When Davis Jr. was commissioned as a second lieutenant with the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment, the Army had only two Black line officers: Both Davises, father and son. Davis Jr. would even go on to teach military science at Tuskegee Institute, a position his father had also held.

LEADING THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN

Thanks to the collective efforts of many pioneering Black aviators and activists—and some convincing from Davis Sr., newly promoted to the rank of Brigadier General—President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the creation of an all-Black Army flying unit in 1941. As the only active Black West Point graduate, Davis Jr. was a natural choice to lead the squadron. It was more than just the realization of his dream of becoming a pilot; in leading the unit, he had an opportunity to undermine segregation and show the world that African American pilots were just as capable as white ones.

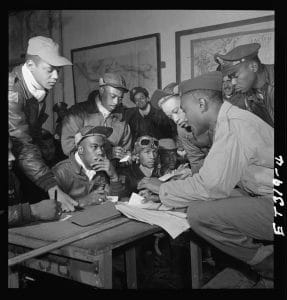

He began his flight training at Tuskegee Army Air Base in May 1941, and was the first Black officer to solo an Army Air Corps plane. On March 7, 1942, Davis Jr. and four other Black officers earned their wings. Throughout the course of the war, over 1,000 more Black cadets would graduate from the program to become “Tuskegee Airmen,” the nation’s first Black combat pilots. Davis Jr. would command the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first and oldest of the Tuskegee Airmen units. A year later, he took command of the 332nd Fighter Group, leading all Black military aviators.

The war record of the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd—which included the re-named 99th Fighter Squadron and three other squadrons—is legendary. The unit supported the Allied invasion of Sicily and provided air cover for much of the fighting throughout Italy. They flew 15,000 sorties, downed 112 enemy aircraft, destroyed 273 planes on the ground, and even sunk an enemy destroyer. Davis Jr. personally led 67 of those missions, including an incredible round-trip bomber escort over Berlin in which the Tuskegee Airmen took down three of the new, faster German jet fighters without losing any fighters of their own. Davis himself was awarded the Silver Star and the Distinguished Flying Cross for his service.

Capt. Davis Jr. climbs into his aircraft in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1942. (Office of War Information/Public Domain Photo)

But Davis Jr. and the Tuskegee Airmen weren’t just fighting the Axis in the skies over Europe—they were also battling segregation, discrimination, and bigotry, sometimes from their own commanders. Davis Jr. would later write in his autobiography that “All the blacks in the segregated forces operated like they had to prove they could fly an airplane when everyone believed they were too stupid.” Shortly after the their arrival in the Mediterranean Theatre, the commander of the unit Davis and his men were attached to complained that the Black pilots were “not of the fighting caliber of any squadron in this Group;” that officer’s superior agreed, saying, “The consensus of opinion seems to be that the Negro type has not proper reflexes to make a first-class fighter pilot.” A recommendation was made to pull the Tuskegee Airmen from combat, and a War Department commission was set up to investigate.

Davis Jr. knew his men were being judged unfairly, and organized a press conference at the Pentagon to defend them. Testifying before the War Department commission, he explained the unfair odds the Tuskegee Airmen were up against, flying against experienced enemy pilots in outdated aircraft. Because they were short-staffed, they often had to fly more missions than their white counterparts, too. He argued that his men were just as eager to fight as white pilots. Thanks to his impassioned efforts, the committee found no difference in performance between white and black air units and decided to keep the Tuskegee Airmen in the fight.

Despite having to put up with these extra pressures, the unit’s stellar accomplishments paved the way for post-war desegregation, as the military could no longer make the old racist claim that African Americans were inferior soldiers.

THE AIR FORCE INTEGRATES

After the war, Davis Jr. took command of the 477th Composite Group and became base commander at Lockbourne Army Air Base in Ohio. Despite initially facing bigotry, Air & Space Forces Magazine reports that his professionalism won over the locals and resulted in the base becoming “a treasured part of the community.” Most of the civil servants working at the base were white, while their superiors were Black—a unique situation in America at the time. “For centuries people said whites would never work for blacks, but at Lockbourne several hundred whites worked professionally and well for Davis and the Tuskegee Airmen,” Air & Space Forces wrote.

When the Army Air Corps split off into the U.S. Air Force in 1947, Davis Jr. joined, hoping to push the new branch to desegregate. In fact, Air Force Lt. Gen. Idwal H. Edwards was already using the war record of Davis Jr. and the Tuskegee Airmen to make the argument for Black and white airmen to serve together. Finally, in 1948, President Truman ordered the desegregation of the military, and the new Air Force was the first branch to integrate. Davis Jr. was one of the leaders who helped write the Air Force’s integration plan.

Davis Jr., then a Colonel, leads a formation of F-86F Sabres during the Korean War in 1953 (Public Domain photo)

That summer, Davis Jr. became the first Black officer to attend the Air War College, a necessary step to promotion that had previously been barred to African Americans by segregation. While his attendance represented another barrier broken, Davis Jr. still had to deal with racial discrimination; since the college was in Montgomery, Alabama, Air & Space Forces reports, many of the restaurants, shops, and services in the city were closed to him. “He and Mrs. Davis could anger the bigots among Montgomery’s whites just by driving a late-model automobile,” the magazine wrote. Once he graduated, Davis Jr. moved on to a job at the Pentagon, where he was “the impetus behind the Air Force Thunderbirds aerial demonstration team.”

Davis Jr.’s assignments over the next few years saw him leading integrated units, further proving that desegregation was a success and white soldiers would loyally follow Black leaders. After moving to Washington, he supervised white officers and enlisted men in his role as chief of Air Force Operations’ Air Defense Branch. In 1953, as the Korean War raged half a world away, he was placed in command of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, where he once again saw combat. There were thousands of men under his command, and most of them were white.

After the Korean War, Davis Jr. was transferred to Tokyo to train the Far East Air Forces. It was there in 1954 that he was awarded his first star as a Brigadier General, becoming the first African American general in the Air Force.

General Earle Everard Partridge pinning a general’s star on Benjamin O. Davis in 1954. (Public Domain photo)

COLD WAR, RETIREMENT, AND POST-MILITARY CAREER

Davis Jr. would go on to serve in a number of prestigious roles in the Air Force. First, he was made vice-commander of the 13th Air Force and transferred to Taiwan. There, he was tasked with creating an air defense force from scratch to defend the tiny island in the event the mainland Chinese Communist forces attacked. It was new territory for the seasoned general, as the unique position required “sophisticated diplomatic skills.”

Two years later, he had built a significant force to deter a possible invasion and built a strong camaraderie with the Chinese Nationalist forces. Lt. Gen. Jiang Jingguo said of Davis, “Standing on the front line of the free world, you have contributed greatly to the strengthening of the force of freedom, and to the protection of our common interests. I wish to include herewith our sincere appreciations to you for your great assistance in the air defense of this country. You have won for you far more than professional appreciations among your friends in Free China.”

In the years that followed, Davis would serve in high leadership roles in Germany, Korea, and back home at Air Force Headquarters in the United States. He received his second star as a Major General in 1959, and his third as a Lieutenant General in 1965. While commanding the 13th Air Force in the Philippines in 1967, he led some 55,000 men, many of whom were fighting in Vietnam. In 1968, he returned to the U.S. as Deputy Commander in Chief of U.S. Strike Command. He retired in 1970 after over 33 years of service.

Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. in 2002, shortly after receiving his fourth star. (USAF/Public Domain Photo)

Davis held a number of important safety and leadership positions following his military service, including: Director of Public Safety in Cleveland, Ohio; Director of Civil Aviation Security, where he oversaw the federal Sky Marshal program; and as Assistant Secretary for the U.S. Department of Transportation.

There was one last honor remaining for Davis. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Davis his fourth star, promoting the retired general to the rank of full General. At the ceremony, President Clinton said Davis Jr. was “a hero in war, a leader in peace, a pioneer for freedom, opportunity, and basic human dignity. He earned this honor a long time ago.”

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. died in 2002 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.