Willa Brown led a life of firsts, breaking several color barriers in aviation and politics. She was the first African American woman to earn her pilot’s license in the United States, and later became the first African American woman to run for Congressional office. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about this remarkable pilot, flight instructor, aircraft mechanic, and civil rights pioneer and her impact on aviation history.

Above photo: A young Willa Brown poses with aircraft in Chicago in the 30s (Public Domain Photo).

Willa Brown, Pioneering Aviator

EARLY LIFE AND AVIATION IN CHICAGO

Willa Beatrice Brown was born in Glasgow, Kentucky in 1906. Her parents moved the family to Indiana, where Willa excelled in school. She went on to graduate from what would later become Indiana State University and become the youngest teacher in the Gary, Indiana school system at age 21. Her love for teaching followed her throughout her entire life, but during the difficult years of the Great Depression, Brown also worked as a postal clerk, secretary, and lab assistant to support herself. In 1932, a position as a social worker with the Works Progress Administration would bring her to a city that was fast becoming the hub for black aviation in America—Chicago.

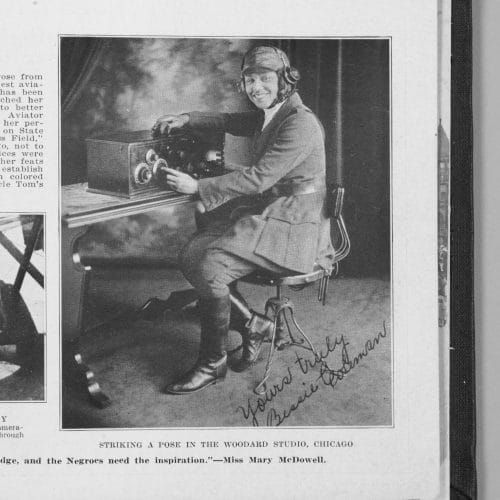

Brown was fascinated by aviation and by the legacy of another Chicagoan, Bessie Coleman, the first black woman to fly a plane. Though Coleman died tragically in an air accident in 1926, she had inspired the next generation of black aviators—among them John C. Robinson and Cornelius Coffey, who founded the Challenger Air Pilots Association for black pilots barred from other flying clubs as well as a flight instruction and ground school program at Harlem Field on Chicago’s southwest side.

Brown met Robinson in 1934 and joined the Challenger group shortly after, beginning her flight instruction with Robinson and Coffey as her teachers. It was a busy time for Brown, who was simultaneously studying to become a pilot, getting a Masters Mechanic Certificate from Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical University, and earning an MBA from Northwestern University.

When Brown earned her pilot’s license in 1937—airman’s certificate No. 43814—she became the first African-American woman to earn a U.S.-issued pilot’s license (her hero Bessie Coleman had been forced to get her license in France because American flight schools had not accepted women or African-Americans at the time).

AVIATRIX EXTRAORDINAIRE

Now equipped with a pilot’s license, the lifelong teacher set out to instruct more black fliers and mechanics and solidify a place for African Americans in the growing field of aviation. She would go on to teach about 2,000 students over the course of her instructor career. Along with Coffey (who she would later marry), Brown co-founded the Coffey School of Aeronautics in 1937 in the Chicago suburb of Oak Lawn. It was the first black-owned flight training school in the country, and unlike other flight schools of the era, it accepted students regardless of race or gender.

In addition to teaching flying and mechanical lessons, Brown also ran the business side of the school as well as the airfield’s luncheonette. In the words of her former student Chauncey Spencer, “Willa was persistent and dedicated. She was the foundation, framework, and builder of people’s souls. She did it not for herself, but for all of us.”

Lola Albright (left) and Willa Brown (right) pose in front of an airplane (Public Domain Photo).

The charismatic Brown worked to raise the Coffey School’s profile. To gain publicity for an airshow put on by the school, she visited the office of black-owned newspaper The Chicago Defender, where her confident manner and pilot’s uniform made quite an impact on editor Enoch Waters. “All the typewriters, which had been clacking noisily, suddenly went silent” when she entered, Waters claimed. Brown introduced herself as an “aviatrix” and told Waters all about the school’s work.

“Fascinated by both her and the idea of Negro aviators, I decided to follow up the story myself,” Waters later wrote. “So happy was Willa over our appearance that she offered to take me up for a free ride. She was piloting a Piper Cub, which seemed to me, accustomed as I was to commercial planes, to be a rather frail craft. It was a thrilling experience, and the maneuvers—figure eights, flip-overs, and stalls—were exhilarating, though momentarily frightening. I wasn’t convinced of her competence until we landed smoothly.”

With the press—and crowds of thousands of airshow spectators—thrilled by her and her students’ aerial abilities, Brown and her fellow aviators next set out to change the U.S. government’s attitude toward African American pilots.

FIGHTING FOR BLACK PILOTS IN THE MILITARY

The fight for African-American inclusion in the armed forces was an uphill battle, with black pilots still barred from serving in the 20s and 30s. A 1925 Army War College Report had called African-Americans “inferior” to their white counterparts when it came to serving in the military, and the discriminatory “findings” therein would go on to dictate Army leaders’ prevailing attitudes through the beginning of the Second World War.

While continuing to teach pilots in Chicago, Brown and Coffey co-founded the National Airmen’s Association of America in 1939 to help get more African-Americans involved in aviation and aeronautics on a national level; the group would eventually grow to over 2,000 members, with chapters across the Midwest and East Coast. Through both the NAAA and the Coffey School, Brown sought to convince the government to allow black aviation cadets to join and serve. Thanks to Brown’s growing profile and vocal support—and with the nation facing a pilot shortage on the brink of WWII—the Coffey School was chosen to train black pilots for a war-preparedness effort called the Civilian Pilot Training Program, with Brown serving as director and training coordinator.

As civil rights leaders continued to push for African American inclusion in the military, Brown wrote to none other than First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for help. “During the past three years I have devoted full time to aviation, and for the most part marked progress has been made,” reads Brown’s letter, which you can read in its entirety here. “I have, however, encountered several difficulties—several of them I have handled very well, and some have been far too great for me to master.” The First Lady would go on to help remove some of the difficulties for black pilots that Brown alluded to, lobbying President Franklin Roosevelt to end restrictions on African-Americans serving in the military.

Lieutenant Willa Brown in her Civil Air Patrol uniform (Public Domain Photo).

When the Army Air Corps set up a training program for black pilots at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the Coffey School was selected to provide trainees. Some 200 of Brown’s students would join that program and go on to become Tuskegee Airmen, the first African-American military pilots to take on the Nazis in Europe. Despite this amazing progress, black pilots were still only allowed to serve in segregated units, which disappointed Brown and Coffey.

During World War Two, Brown sought to serve more directly. She attempted to join the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, but was rejected due to her race. Undeterred, she joined the Civil Air Patrol, which helped organize civilian aviation resources for the war effort. According to the National World War Two Museum, the group “flew missions in anti-submarine and border patrols and fulfilled much-needed courier services.” Brown was commissioned as a Lieutenant, becoming the Civil Air Patrol’s first African American officer.

Finally, in 1948, the dream of Brown, Coffey, and their fellow aviators was realized: President Harry Truman ordered all branches of the military to desegregate. It wouldn’t have been possible without the tireless and persistent advocacy of Willa Brown.

MORE FIRSTS

A drawing of Lt. Willa Brown by Harlem Renaissance artist Charles Henry Alston (Public Domain Photo).

Coffey and Brown would close their school and divorce shortly after the end of the war in 1945, but Brown wasn’t yet finished breaking barriers. In 1946, she became the first African American woman to run for Congressional office, running in the primary for the Illinois 1st Congressional District. She ran again unsuccessfully in 1948 and 1950, with part of her platform including the creation of a black-owned and operated airport in Chicago and improving opportunities for African Americans in general.

She continued to teach business and aeronautics in Chicago Public Schools until her retirement in 1971. In recognition of her pioneering work in aviation, the Federal Aviation Administration appointed her to their Women’s Advisory Board in 1972 as the first black woman to serve on that committee.

Brown continued to be a leading voice in the struggle for civil rights up until her death in 1992. She’s buried in Lincoln Cemetery, sharing a final resting place with her hero and fellow aviation pioneer Bessie Coleman.