William J. Powell was a tireless promoter of African American participation in the budding field of flight. In an era when daredevil pilots captured the imagination of the masses, Powell recognized that aviation also presented great opportunities for African Americans and did all he could to encourage more black fliers to take to the skies. In honor of Black History Month, read on to learn about this amazing pilot, entrepreneur, and author!

WILLIAM J. POWELL URGES AFRICAN AMERICANS TO ‘FILL THE AIR WITH BLACK WINGS’

Early life and first flight

“There is a better job and a better future in aviation for Negroes than in any other industry, and the reason is this: aviation is just beginning its period of growth and if we get into it now, while it is still uncrowded, we can grow as aviation grows.” — William J. Powell, Black Wings

William J. Powell was born in 1897 in Henderson, Kentucky. When he was just eight, his family moved to Chicago, a city that would go on to be a hub for early black aviators like Bessie Coleman and Cornelius Coffey. Powell, a talented student, was described by Air Facts Journal as “thin, lanky, and invariably well-dressed” and by National Air and Space Museum curator Von Hardesty as “a natural-born entrepreneur.” He enrolled in the engineering program at the University of Illinois at 17, but his studies were cut short by World War I.

Powell served in the segregated 370th Infantry Regiment—the only regiment in the war commanded entirely by black officers—in France, where a poison gas attack left him with health issues for the rest of his life. After the war he returned to university to finish his engineering degree and found success early in his career by operating a chain of gas stations and auto parts stores on Chicago’s South Side.

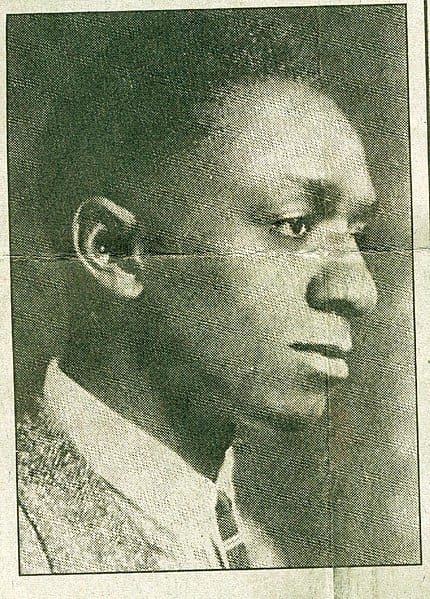

William J. Powell in his U.S. Army uniform. (Public Domain photo)

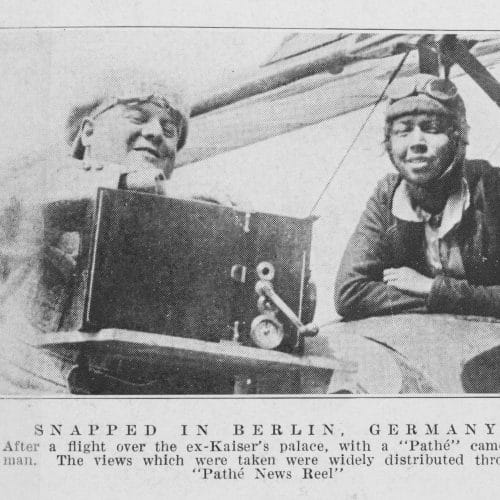

As a successful business owner, Powell had the money to travel to Paris for an American Legion convention in 1927 with other WWI veterans. Just months earlier, international aviation hero Charles Lindbergh had made history there, finishing the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic by landing at Paris’s Le Bourget Airfield. It marked the peak of aviation’s “Golden Age,” and the masses—Powell included—were fascinated by the adventures of daredevil aviators. While in Paris, Powell took a leap of faith and went to Le Bourget hoping someone would take him up in an airplane.

Powell got his wish, and by the time his plane landed after a tour over the city that included circling the Eiffel Tower, he knew he was destined to become a pilot himself. However, he wasn’t only thinking of his personal path—he saw the open blue skies and the new industry growing around aviation as an opportunity for his entire race. At that time in the 20s, African Americans were barred from many industries due to segregation and Jim Crow laws, and in addition to those racial barriers, they would soon be hit hard economically as America plunged into the Great Depression. Powell began to realize that aviation could provide a means to lift up not just an individual, but an entire community. As the African American Registry writes, “Powell meant to fly around Jim Crow … By taking hold of the embryonic flight industry, Black Americans could build their own economic independence.”

LEARNING TO FLY—AND BUILDING A COMMUNITY

“Stimulating interest in aviation among Negroes would not be such an arduous task were it not for stumbling blocks which seriously menace the Negro’s entry into any line of commercial endeavor. Skepticism, superstition, mistrust, jealousy, lack of co-operation, lack of preparation, race prejudice, and lack of finance have caused many a young Negro to turn away from some field of commercial endeavor with disgust.” — William J. Powell, Black Wings

Upon his return to the United States, Powell started applying to flight schools in the Chicago area—and even to the Army Air Corps—but was repeatedly rejected due to his race. Finally, in 1928, he was accepted into the Warren School of Aeronautics in Los Angeles. He sold his businesses, uprooted his family to California, and began his pilot’s journey.

He would eventually earn his pilot’s license in 1932, but even before completing his training, Powell began to build a strong community of African American aviators in his new home city. One thing they all had in common was a reverence for trailblazing aviator Bessie Coleman, who had drawn crowds of thousands to see her perform at airshows before her tragic death in an air accident in 1926. “Because of Bessie Coleman, we have overcome that which was much worse than racial barriers,” Powell later wrote. “We have overcome the barriers within ourselves and dared to dream.”

Powell formed the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in 1928 for his fellow black aviation enthusiasts and started the Bessie Coleman Flying School, making Coleman’s dream of a training center for black pilots a reality. James H. Banning, the first African American to be issued a pilot’s license in the U.S., became the school’s first instructor, and the group set to work raising awareness for black aviation.

One way Powell and his Aero Club compatriots gained attention for their field was by putting on air shows featuring black pilots and parachute jumpers. On Labor Day of 1931 at the Los Angeles Eastside Airport, they put on the nation’s first all-black air show for a crowd of 15,000. Just a few months later, they held another, calling it the “Colored Air Circus.” This time, Powell drew wider attention by making the show a benefit for Los Angeles’s unemployed community, then growing due to the Depression. This air show drew 40,000 and featured the largest formation of black aviators in the air at one time. Powell called them The Five Blackbirds, and used the success of the event to plan more air shows across the country.

WRITING “BLACK WINGS” AND RAISING NATIONAL AWARENESS

“We have lost money, we have bought airplanes, we have flown them, we have cracked them up, and we’re flying them some more, for the job must be done. No one is making us do it. We are flying of our own free will and accord, for the conquest of the air is an accomplished fact.” — William J. Powell, Black Wings

In 1934, according to the National Air and Space Museum, there were only 12 licensed African American pilots out of a total of 18,041 flying in the United States. It was against this backdrop that Powell wrote his groundbreaking semi-autobiography, “Black Wings,” to encourage more African Americans to get involved in aviation not just as pilots but as engineers, mechanics, aircraft designers/builders, and business leaders.

In “Black Wings,” Powell used the fictional character of “Bill Brown” as a stand-in for himself, writing about his struggle to become a pilot and the other early African American aviators he met. He used his story to lay out his beliefs that aviation provided African Americans a golden opportunity to “carve out [their] own destiny.” The book was dedicated to the memory of Bessie Coleman.

The book was just one of the ways Powell would seek to put black aviation on a national stage. In 1935, he produced a film called “Unemployment, the Negro, and Aviation.” The film centers on a black college graduate looking for a job but finding many avenues closed by discrimination—until one day he sees a poster featuring Powell’s call for more black aviators and decides to become a pilot. Powell also published a newsletter called Craftsmen Aero News, and enlisted famous friends including boxer Joe Louis, actress Lena Horne, and musicians Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington to drum up support for African American aviation efforts.

William J. Powell. (Public Domain photo)

Powell had grand plans for creating an entire black aviation industry, rather than waiting to be accepted by whites—he wrote in Black Wings, “I do not ally myself with [the] Negro who begs a White man for his job. I ally myself with that … young progressive Negro who believes [he] has the brain, the ability, to carve out his own destiny.” It was in that spirit that he created the first black-owned aircraft manufacturing company, Bessie Coleman Aero.

Black Past described Powell’s vision for an African American-led aircraft industry: “Powell envisioned Bessie Coleman Aero as a firm that would hire African Americans to design and build aircraft which would be flown by black pilots and serviced by African American mechanics. He imagined parallel black firms that would build and manage airports. These businesses, according to Powell, would serve all Americans, not just African Americans.” Sadly, the Bessie Coleman Aero project would not survive the economic turmoil of the Great Depression—along with a second firm, which Powell had also named Black Wings.

Powell died in 1942 at just 45 years old, likely from complications related to his World War I injuries. Though his life was cut short, his dream lived on—just one year after his death, the first black military pilots would take on the Nazis in the skies over Europe, serving with distinction and opening even more avenues for black aviators. Through his tireless networking, promoting, and entrepreneurship, Powell had paved the way for a new generation of African American pilots.

READ MORE ABOUT BLACK HISTORY AND AVIATION

Bessie Coleman

Cornelius Coffey